Damien F. Mackey

“Achior is not simply a foil for the other characters in the book,

but acts as a double or alter ego of the character of Judith”.

A. Roitman

P. M. Venter begins with the understandable – but I think, wrong – presumption that Achior is an Ammonite, titling his article:

The function of the Ammonite Achior in the book of Judith

Whilst this is quite a reasonable conclusion to make, considering the fact that the text of the Book of Judith, as we currently have it, will refer to him as “Achior, the leader of all the Ammonites” (Judith 5:5) and ‘Achior, you Ammonite mercenary’ (words of Holofernes) (6:5).

Confusingly though, a mere 3 verses before this (6:2), Holofernes will differently describe him as ‘Achior and you mercenaries of Ephraim’.

And that, I believe, is the right designation for Achior, “Ephraim”, given my identification of Achior with Ahikar, the nephew of Tobit, who was indeed a northern Israelite (Tobit 1:22): “Ahikar was my nephew and one of my family”.

Is Ahikar not even called, in the Douay version of Tobit, Achior?

P. M. Venter writes:

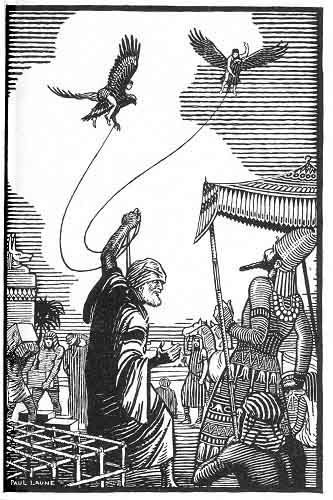

The character of Achior is depicted in several places in the narrative of Judith. We meet him the first time when Holofernes, the ranking commander of Nebucadnezzar [sic], king of the Assyrian, prepares for war against the Israelites of Judah. He is advised by Achior, the leader of the Ammonites, that these people living in the hill country worship the God of Heaven11. Achior suggests to Holofernes to abstain from attacking them (Jud 5:24) because their lord and god will defend them (Jud 5:1–21).

Holofernes interprets this advice as an insult and bans Achior to the Israelite town of Bethulia where he would finally be killed along with the inhabitants when Holofernes’ army ravage the city (Jud 6:1–10).

Achior is next tied up and left at the foot of the hill at Bethulia. Having been untied again and brought into the town, he reports on Holofernes’ offensive against the Israelites and his effort to discourage the Assyrians to fight against God’s people. He is then taken to the house of the magistrate Uzziah where a banquet is held and the inhabitants pray all through the night for God’s help (Jud 6:11–21).

The first time we hear of him again is after Judith decapitates Holofernes and returns to Bethulia with his head in a food sack. Judith summons Achior the Ammonite to see and recognise the one who despised Israel. Either identifying the face of Holofernes12 or witnessing the result of his former warning to the deceased, Achior faints, is picked up and throws himself at Judith’s feet and does obeisance to her. He requests her to report on what she did at [Holofernes’] … camp. He understands these events as God’s beneficial deeds to Israel. It moves him to believe in God completely. He is then circumcised and admitted to the community of Israel (Jud 14:5–10).

The narrator depicts the character of Achior by setting him in relationship to the other characters of the story13. In the conflict with Holofernes he witnesses to the God of heaven and thereby provokes his ordeal to die along with the people whom he defends. The narrator uses his character here to introduce the plot of the story and to indicate his viewpoint that nobody, not even the mighty Assyrians, are able to withstand the God of Israel. In the incident where he informs the inhabitants of Bethulia of Holofernes’ offensive, Achior acts as agent not only to prepare them for the onslaught, but he also directs them to their God for help. Again he functions as an expression of the narrator’s theological viewpoint. He gives a leading role in the events to a former pagan character [sic].

Comparing the role of secondary male characters in the stories of Judith and Jael, White (1992:10) indicates that Achior ‘is loosely modelled on the character of Barak in Judges 4 and 5’. Achior’s function in the story is the same as that of Barak. He acts as a foil for the leading female character, Judith. In both cases the male ‘characters leave the stage, only to return after the heroine has completed her action’ (White 1992:10). This technique focuses on the women as the heroin [sic], confirming ‘Yahweh’s use of a weak, marginalised member of the society in order to save it’ (White 1992:10). Although being a foil Achior plays a similar role as Judith in the narrative, both indicate persona non grata who are the heroes of the story. White (1992:14) indeed remarks that the parallels between the Judith and the Jael stories (Barak and Achior) go beyond correspondence in structure, plot and character.

In his study of the role and significance of Achior in the book of Judith, Roitman (1992:32) indicates ‘an especially intriguing structural relationship and a subtle complementarity between Achior and Judith’14. Achior is not simply a foil for the other characters in the book, but acts as a double or alter ego of the character of Judith. Thematically as well as functionally he is used in the narrative as the mirror image of Judith (cf. Roitman 1992:38)15. To study Achior and Judith’s respective functions in the narrative, Roitman (1992:33–38) divides the story into five stages. Initially Achior the Ammonite is the pagan [sic] soldier whilst Judith is the timid Judaean widow living a secluded life. Undergoing a change in their respective fundamental traits, the story ends where Achior becomes a mere citizen (as opposed to a leader) in Bethulia. He is circumcised and accepted in the society as a co-believer in God, whilst Judith changes into a military hero and commander in Israel and is hailed for her piety and role as the saviour of her people. Although coming from different walks of life both belong to the same community of faith, in the end having both contributed to the solution of the intrigue in their different ways.

His analysis brings Roitman (1992:39) to the question why the author portrayed Achior as the soldier and Ammonite as the thematic and functional counterbalance of Judith? It could have been done for more than purely literary reasons. It is possible that the story is the result of an underlying ideology of proselytism in this nationalistic book. Presumably the author wanted:

to teach us through this very sophisticated technique that a righteous pagan [sic], even one who belongs to the hateful people of Ammon, is, essentially, the parallel and complement to a complete Jew by birth, and that he is able to perfect his condition by believing in God and joining the people of Israel through conversion. (Roitman 1992:39)

Roitman (1992:39) is of the opinion that this ‘subtle ideology of proselytism’ substantiates his thesis that the traditions about Abraham were used by the author to depict the characters of both Judith and Achior. Referring to the witness of Achior in Judith 5:6–9 as ‘the Abraham section’, Roitman (1992:45, n. 51) comes to the conclusion that the book of Judith advances the doctrine that ‘the righteous pagan who converts to Judaism would also have, as the native Jew has, Abraham as his model or “father”‘ (Roitman 1992:40).

Judith 5:6–9 refers to the Israelites as the descendants of the Chaldeans who did not want to worship the gods of their ancestors in Chaldea. Abandoning the way of their ancestors they worshiped the ‘God of Heaven’. They were driven out by the Chaldeans from the presence of their gods and fled to Mesopotamia where they settled for a long time before moving to the land of Canaan. This description agrees only with the second item of the patriarchs in the Gattung of ‘historical review’ as indicated earlier in the article. As Israel is presented as a collective unit in Judith 5:6–9, Roitman’s acceptance of Abraham can be questioned. Other possibilities for the modelling of Achior should also be considered.

Moore (1985:163–164) indicates that Achior was a wise man, also in the technical sense of the word. He is depicted as an Ammonite form of Ahikar. Ahikar was a:

famous pagan wise man who was an advisor to the Assyrian kings Sennacherib and Esarhaddon and the reputed author of a wisdom book containing a number of proverbs and fables. (Moore 1985:163)

Mackey’s comment: Achior was indeed the wise sage Ahikar, but he was not an Ammonite.

I think that “Elamite” ought perhaps to be substituted for “Ammonite” wherever the latter occurs in the text, considering that Elam (“Elymaïs”) was where Ahikar had ruled on behalf of the neo-Assyrian kings. Cf. Tobit 2:10: “Ahikar took care of me for two years until he went to Elymais” and Judith 1:6: “Arioch, king of the Elymeans” (read “Achior governor of the Elamites”).

Venter continues:

The profile of this Ahikar as a good and just pagan fits the Achior of Judith. In the contemporary book of Tobit the Assyrian Ahikar has been Judaised. Moore agrees with Cazelles’ argument that Achior is an ethnic transformation [sic] of Ahikar. Roitman (1992:42) refers to this ‘Ahikar theory’ proposed by Moore and Haag, but strongly rejected by Steinman. Otzen (2002:108) doubts the theory that Achior and Ahikar can be identified with each other. His argument is based on the difference in status between the two: Ahikar is a Jew by birth, whilst Achior is a ‘genuine pagan’. Roitman (1992:32) criticises the aforementioned scholars for failing to see Achior’s ‘overall complex function and to integrate it into the structural framework of the story’16. Although it is probable that the tradition of Ahikar served as model for characterising Achior, it is necessary to rather study the narrator’s transformation of this figure in his story.

Moore (1985:167) calls Achior an ‘Ammonite “Balaam,” a Gentile who must speak only good about Israel’. The Ammonite Achior17 may have been based upon the tradition of Balaam son of Be’or (Nm 22–24)18. In the Deir Allah inscriptions he played an important role in the Ammonite literary tradition from at least 700 BCE.

Moore (1985) explains:

[J]ust as Balaam of Deir Allah brought to his people a communication from the gods, so later on another Ammonite, Achior, tried to enlighten his people about the nature and will of Israel’s God. (Moore 1985:167)

Moore correctly identifies Achior as a messenger of the gods, but does not ask the question of the role Achior plays in the Judith narrative and how his message fits into a totally different situation.

This brings us back to the question of intertextuality. Not only the probable source of the Achior character, but also the ‘stance’ and ‘filter’ (Stahlberg) is to be studied to identify the ideological purpose of the author in using the character of Achior.

Mackey’s comment: Achior does not compare at all well with Balaam.

Balaam was an inveterate pagan prognosticator who receives a very bad press in both the Old and New Testaments, and who comes to a sticky end.

Deir 'Alla inscription and the historical Balaam son of Beor

Achior was a wise Israelite, an almsgiver, who admittedly had to undergo a conversion (who doesn’t?), but who was exonerated and came out into the light.

See e.g. my article:

"Nadin" (Nadab) of Tobit is the "Holofernes" of Judith