Part Two:

Were northern Israelite captives involved?

“The city of Halah, or Halahhu, in which Israelites were resettled was therefore located

just outside Sargon’s new capital city complex. Amazingly, in spite of this knowledge, apparently no one -- historian, scholar, or archaeologist -- has ever examined

this Halahhu city mound area. There seems to be no effort to trace lost Israel!”

Jory Steven Brooks

The only preliminary comment that I (Damien Mackey) would need to make regarding this interesting piece by Jory Steven Brooks:

The Book 2 Kings ch.17 v.6 reveals that one of the places to which Israel was transplanted was called, "Halah." Little has been written about this in Christian literature, and some scholars plead ignorance as to the correct location of this place of exile. However, the Anchor Bible Dictionary (III. 25) tells us that this word matches letter for letter with the Assyrian district of "Halahhu," except for the doubling of the last "h" and the addition of the characteristic Assyrian "u" case ending. The latter is not unusual, because the Biblical Haran (Genesis 11:32, 12:4-5, 28:10& 29:4) appears in Assyrian as "Haranu", and Ur, the birthplace of Abraham (Genesis 11:28 and 31, 15:7 and Nehemiah 9:7), is written as Uru.

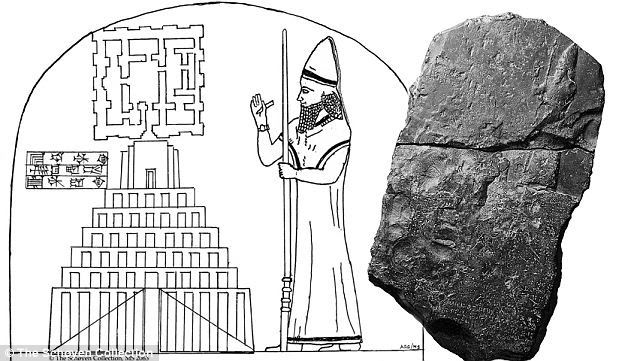

This district of Halahhu was located north-east of the city of Nineveh in northern Assyria. A map shown in the Rand-McNally Bible Atlas (1956) indicates that Halahhu covered all of the area from Nineveh to the Zagros Mountains to the north and north-east (p. 244-5). In the midst of this district, King Sargon II purchased land along the Khosr River from the inhabitants of the small non-Assyrian town of Maganuba to build a new capital city. This new city was named Dur-Sharrukin, the Fortress of Sargon; it is better known today as Khorsabad after the modern small village of that name built on part of the ruins.

Halahhu was also the name of a city as well as a district. The Rand-McNally Bible Atlas (p. 297-8), informs us,

"Halah lay northeast of Nineveh, which city at a slightly later day had a gate named the 'gate of the land of Halah' [Halahhu]. Since there is reason to believe that the city lay between Nineveh and Sargon’s new capital [Khorsabad], the large mound of Tell Abassiyeh has been nominated for it. ….."

The city of Halah, or Halahhu, in which Israelites were resettled was therefore located just outside Sargon’s new capital city complex. Amazingly, in spite of this knowledge, apparently no one -- historian, scholar, or archaeologist -- has ever examined this Halahhu city mound area. There seems to be no effort to trace lost Israel! Is it perhaps because of the popular myth in books and journals that no Israelites were ever exiled or lost?

The reasons why Sargon moved the capital of Assyria from Nimrud to the new city of Dur-Sharrukin has been a fertile subject for speculation among scholars. Historians believe that his predecessor, Shalmaneser V, was murdered in Palestine during the siege of Samaria. The exact date of Shalmaneser’s death is unknown, but it may have been in 721 BC, because Sargon claimed to be the conqueror of the capital of Israel. If Sargon was in some way involved in the conspiracy that enabled him to seize power (an obvious supposition), he may have disdained ruling in the palace of his predecessor. Another possibility is that Sargon wished to expand the borders of Assyria northward into the sparsely inhabited Zagros Mountains, its foothills and valleys, to strengthen his northern border.

Whatever the reasons, a marvellous palace complex came into being almost a mile square, twelve miles north-east of Nineveh along the Khosr River. It was a massive building project. Assyrian scholar William R. Gallagher tells us that in Assyrian terms, Dur-Sharrukin was 2,935 dunams in size, compared to the city of Jerusalem at only 600 dunams (Sennacherib’s Campaign, p. 263). Yet this accomplishment was in spite of the fact that Assyria had a massive labour shortage:

"At least two letters to Sargon indicate a shortage of manpower. In one letter the sender complained that the magnates had not replaced his dead and invalid soldiers. These amounted to at least 1,200 men. The second letter, probably from Taklak-ana-Bel, governor of Nasibina, reports a scarcity of troops" (ibid., p.266).

This labour shortage was partly due to the massive capital building project, but also because of a deadly epidemic resembling the bubonic plague that later raged across Europe in the fourteenth century AD. The Akkadian word for it was "mutanu", the plural of "mutu," meaning death. This epidemic struck not just once, but several times (802, 765, 759, and 707 BC) with deadly effect. Historical records indicate that this plague had so decimated the Assyrian army by 706 BC that they were unable to engage in any military missions at all that year (ibid., p. 267).

The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago carried out an archaeological excavation at the site of Dur-Sharrukin during the years 1930-33, and published an account of their discoveries in a volume written by Henri Frankfort which says the following:

"We know that Sargon used a considerable amount of forced labor in the building of his capital -- captives and colonists from other parts of the empire" (p. 89).

Assyrian scholar Gallagher adds:

"Sargon II’s cumbersome building projects at Dur-Sharrukin had placed a great strain on the empire...Much of the forced labor on Sargon‘s new city was done by prisoners of war. The conditions shown on Sennacherib’s palace wall reliefs for the transport of his bull colossi were undoubtedly the same as in Sargon‘s time. They show forced laborers under great exertion, some clearly exhausted, being driven by taskmasters with sticks" (ibid., p. 265).

Mackey’s comment re: “The conditions shown on Sennacherib’s palace wall reliefs for the transport of his bull colossi were undoubtedly the same as in Sargon’s time”.

Sargon II was Sennacherib:

Assyrian King Sargon II, Otherwise Known As Sennacherib

Jory Steven Brooks continues:

A text inscribed upon a carved stone bull at Dur-Sharrukin states,

"He [Sargon] swept away Samaria, and the whole house of Omri" (Records Of The Past, XI:18).

The "House of Omri" was the Assyrian designation for Israel, and was spoken with a guttural applied to the first vowel, so that it was pronounced "Khumri." Following Sargon’s terse statement was a notice of the building of the new Assyrian capital city. Construction of Dur-Sharrukin began in 717 BC, only four years after the fall of Samaria, and took over ten years, with ceremonies marking its completion in 706 BC.

Although there is no record of the exact date that the Assyrians marched the Israelite residents of Samaria eastward to Halah(hu), it is probable that Sargon knew from the beginning of his rule (or even before he became king) that he would build his palace in that location. Did he send the Israelites there in order to help build his new city, the capital of Assyria? If not, why were they there during these years of construction? Although proof does not exist at present, the correlation of location and dates, coupled with the great need for labourers, makes it highly probable that YEHOVAH’s people were involved.

And how appropriate was the symbolism resulting from this circumstance! Israel was called to build the Kingdom of YEHOVAH God on earth, but refused. They turned their hearts to false gods and worshipped the work of men’s hands. Because of this, YEHOVAH used the Assyrians, perhaps the foremost pagan idolaters, to punish his people. Those who had been offered the highest honour of building YEHOVAH’s earthly dominion instead were consigned the deepest dishonour of building the earthly dominion of the enemies of YEHOVAH God.

Many of the wall reliefs, stone idols, and other important finds from Dur-Sharrukin are now on display at the Oriental Institute in Chicago. Included is a massive stone winged bull termed in Assyrian, "Lamassu," that formerly stood at the doorway to King Sargon’s throne room. The carving and moving of several of these monstrous stone monuments was undoubtedly one of the most amazing feats of human labour. They were composite figures, with a human face, a body that was part bull, part lion, and wings of a bird. The king was thus symbolically empowered with the formidable qualities of speed, power, and intelligence.